In 1928, Carl Sandburg – under the heading “Tentative (First Model) Definitions of Poetry” in his collection “Good Morning, America” – included this as No. 36 of 38 definitions: “Poetry is the achievement of the synthesis of hyacinths and biscuits.”

Twenty years later, the 70-year-old Sandburg still liked that definition enough to give a lecture for the students of North Park Junior College in Chicago that he also called “Hyacinths and Biscuits.” For a student audience that, like him, was largely Swedish-American, he recited poetry and sang songs from his “American Songbag.” For students at North Park, lectures like this were easy to find nearby; the Tribune ran lists of them most days, some free, some costing as much as 82 cents (around $8 today).

It wasn’t so easy, though, if you were living on a farm in northeast Nebraska, where my mother was born in the same year Sandburg was setting down his 38 definitions. Yet December, 1948, found her not in Wausa (population 700), but in Chicago (population 3.4 million). Three years after her high school graduation as a 16-year-old valedictorian in a class of 27, she had found her way to the second largest city in America.

How in the world had her world changed so dramatically? How did Swedish immigrant Oscar Ottoson figure out that his daughters needed more education, and decided to let them get it in a place that was was 15 times bigger than Omaha (or “just” quadruple the size of the Twin Cities, where he had found his wife some 30 years before)?

Such questions demand reflection in a week when U.S. high school seniors are anxiously checking their mailboxes and phones for word on whether they have been admitted to their “college of choice,” whether its admittance rate is 4.69% or zero or closer to 50. And, as it happens, also in a week where students at another Chicago school, Chicago State, are anxiously checking to see if the university that did admit them will be able to stay open.

In our mobile, connected, urbanized 21st Century context, the world before television is both foreign and remote, more so even than the world before Facebook and the iPhone. Yet for us to get to 2016, America needed to unlock the potential lurking in 43% of its human capital that then was still rural in origin (per the 1940 U.S. Census, vs 19% in 2010), as well as that within the working-class and hard-luck neighborhoods where college had never even been a dream. (More fun facts about America’s farm population in 1940, also from the Census: 79% of rural farms had outside toilets, just 18% had running water, and 31% had electric lights.)

In my mother’s case, leaving the farm came down to encountering someone who had seen the big city and knew what it could mean. His name was Bethel Bengtson, and in 1946 he showed up in Wausa, Nebraska, to take over as pastor of the Mission Covenant Church. An immigrant from Sweden like my grandfather, unlike Oscar he was a graduate of both the junior college and the seminary at the Covenant’s only college, North Park in Chicago.

In my mother’s case, leaving the farm came down to encountering someone who had seen the big city and knew what it could mean. His name was Bethel Bengtson, and in 1946 he showed up in Wausa, Nebraska, to take over as pastor of the Mission Covenant Church. An immigrant from Sweden like my grandfather, unlike Oscar he was a graduate of both the junior college and the seminary at the Covenant’s only college, North Park in Chicago.

In Wausa, he and his wife found my mother not only sitting in the pews, but also – in those postwar days of more demand for education than there were trained educators to provide it – also teaching in one of the several local one-room schoolhouses. This, he decided, was a wasted opportunity.

I can almost hear the discussion on the Ottoson farm, complete with my grandfather’s thick Swedish accent. “Maw,” he’d be saying, “the new preacher says the girls need to go to college in Chicago.” My grandmother, a notorious worrier who fretted whenever Oscar was late coming in from the fields, would have been nervous about this city she had never seen. But ultimately the pastor’s point of view prevailed, and my mom and her older sister Helen sent in their applications.

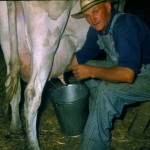

And accepted they were, though their applications would have included few outside activities beyond milking the cows and earning attendance pins at Sunday school. “Ottoson Number One” and “Ottoson Number Two,” the faculty would come to call them. And equally to the point, the younger sister met and became engaged to my dad, a first-generation college student from Calumet High School on Chicago’s South Side who, like Bethel Bengtson, would become a pastor. (Reported the North Park College News one day in 1950, “The other morning in the cafe the boys sang ‘Happy Jewelry Bill’ to Ralph Youngman, who went visiting out Nebraska way over the holidays and gave his girl, Earldine Ottoson, a ring.”)

So the farmer’s daughter and the proofreader’s son took their newly acquired educations and college experiences on the road in their Henry J automobile. Maybe this could happen today . . . I’d argue we need to keep unlocking untapped potential, as well as leveraging proven ability, for society to make similar progress in the next 70 years or so . . . but I have to admit I don’t run into many farm kids on the several college campuses I frequent.

Bethel Bengtson didn’t stay in Wausa for long; in 1950, for his wife’s health, he left for the Covenant church in then-rural Hilmar, California, where it turns out he was pastor to my wife’s parents when she was born a few years later. I met “Pastor Betts” many years later at a summer camp on Portage Lake in Lower Michigan, not long before he died in 1965, having transformed who knows how many other young people by helping them access the educations they’d need to thrive in the American Century.

“Nothing happens,” Sandburg wrote in another context (“Washington Monument By Night,” 1922), “unless first a dream.” He didn’t say whose dream, I notice. Be we educators, politicians, or citizens, our collective job is to turn the dreams of mentors and students alike into a chance to make something happen that further builds the future.