A common first impression of Jack Fuller was that he was soft-spoken. But once anyone started listening to him, it was the message, not the decibel level, that remained at the forefront of memory,

Anecdote: It was January 2010, in the first of his regular appearances in one of my Medill graduate courses for a discussion of his then-about-to-be-published book, “What Is Happening to News.” Winter weather in Evanston is what you’d expect, and the banging and clanging of the radiators in my first-floor classroom were often loud enough to drown out even me, let alone Jack. After class, I apologized for not having foreseen the issue that left the students straining to hear.

“It’s OK,” he said with a smile. “Same radiators as when I was here, and just as loud as I remember.” As was noted in the obituaries that followed his death Tuesday, June 21, Jack graduated from Medill in 1968; Fisk Hall’s status as a Daniel Burnham-designed landmark no doubt was one reason that the issue persisted after 32 years.

I needn’t have worried whether the students had absorbed his words, of course. Later that week I sent him a followup email that read in part, “Not only did the topic interest them; so did you. One student said something to the effect of, ‘You know what was good about him. Some of our professors last quarter would tell stories about the good old days and then tell us they felt sorry that we would never experience anything like it. Mr. Fuller was talking about the future, and telling us we could figure it out!’ ”

Before he challenged others to do that, he did a fair amount of it himself. Much has now been written about this, and about him, both “in print” (here are samples, a New York Sun editorial and a column by John Kass) and in online remembrances by scores of his friends, perhaps none so beautiful as this from a former newsroom clerk–that is, a person who once held the same job in which Jack started at the paper:

Jack’s role in my own career was, of course, central. In the mid-80’s as executive editor he persuaded me to move from my position as suburban editor — where I was working for metro editor Ellen Soeteber, who also died Tuesday — to oversee a group of features sections including food, real estate and travel. Before long, as editor, he decided I should be trained to take over the business section by mastering balance sheets, earnings reports, and economics, and by learning from the people who covered them. And crucially, as publisher, he asked me to share his task of figuring out the future, putting me in position 20 years ago to lead the Tribune onto the Internet.

(And unfortunately in position to disappoint him when he woke up one 1996 morning to see that the New York Times had launched its Web site before we had. Learning not to “let the perfect be the enemy of the good,” we redoubled our efforts, hopeful we could make Jack proud enough to put the disappointment behind him.)

Over the years, our conversations about the future of journalism came to be leavened with discussions of books — Jack the novelist always wanted to know what fiction I was reading, and if I had a discovery he would share his judgment after he had taken it up himself. He seemed pleased when I discovered the intersection in Evanston that gave him the title character for one of his novels, “The Best of Jackson Payne,” and he often reminded me that I had led him to Halldór Laxness and “Independent People.”

Over the years, our conversations about the future of journalism came to be leavened with discussions of books — Jack the novelist always wanted to know what fiction I was reading, and if I had a discovery he would share his judgment after he had taken it up himself. He seemed pleased when I discovered the intersection in Evanston that gave him the title character for one of his novels, “The Best of Jackson Payne,” and he often reminded me that I had led him to Halldór Laxness and “Independent People.”

We both had started at the Tribune as clerks–well, copyboys. We were both trombonists, and he shared the name of his favorite technician. And we increasingly talked about teaching, as he conducted a class in creative writing at the University of Chicago, or developed a lecture to deliver at Columbia University’s journalism school. To think about the immediate future as Jack-less is still almost too much to bear.

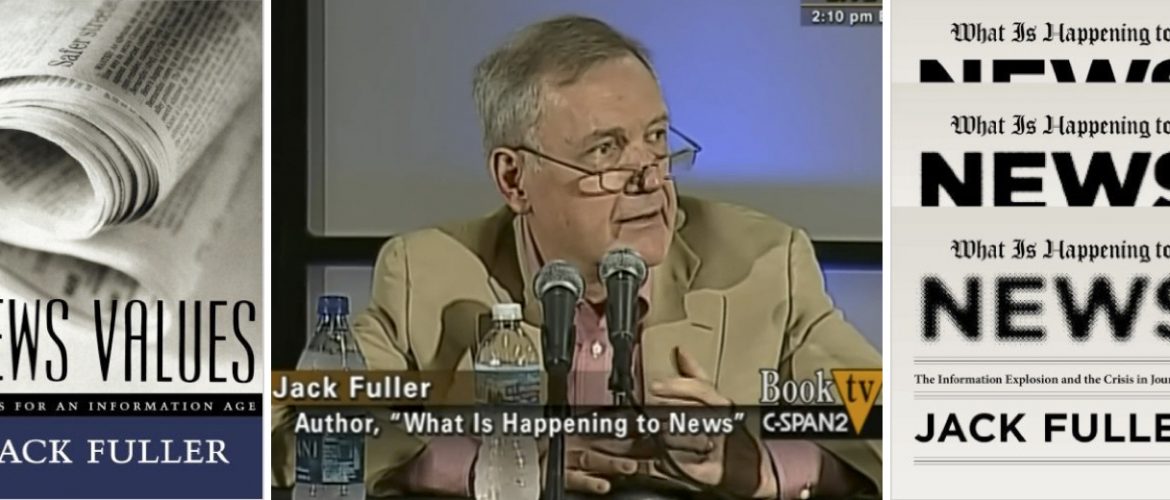

In December 2014 he invited me to appear with him for a public conversation at the Newberry Library, the home of his collected papers. Called “Front Page, Home Page and Beyond: News in the 21st Century,” it was a chance for us to continue working out the ideas he put forth in his first nonfiction book, “News Values: Ideas for an Information Age.” That, too, was an exercise in figuring out the future, as best as any of us could do from the vantage of the mid-1990s, and like “What Is Happening to News,” I continue to use parts of it in teaching both graduates and undergraduates today.

As many of the published tributes this week have made clear, Jack Fuller’s impact is not likely to diminish as long as his writings are read, or as long as those who read them can pass their lessons on to others. I am confident that my students will be among them, because they are already telling me so.