Friday, Nov. 2, was always going to be an interesting night. Back in May, I had agreed to take part in a Northwestern tradition called “Dinner with 12 Strangers,” in which a couple of faculty members, a dozen random students, and some alumni hosts share a meal “in an informal atmosphere that builds Northwestern community and camaraderie,” as my invitation put it.

Recently, just after I learned I’d be dining in beautiful nearby Kenilworth, my second invitation for the evening arrived, promising a somewhat different kind of community and camaraderie: “It’s been 10 years of crummy commutes, celeb meltdowns, 3 a.m. taco runs . . . and we’re just getting started. You’re invited to RedEye’s 10th Birthday Bash. Dress to impress; birthday suits not optional.”

Recently, just after I learned I’d be dining in beautiful nearby Kenilworth, my second invitation for the evening arrived, promising a somewhat different kind of community and camaraderie: “It’s been 10 years of crummy commutes, celeb meltdowns, 3 a.m. taco runs . . . and we’re just getting started. You’re invited to RedEye’s 10th Birthday Bash. Dress to impress; birthday suits not optional.”

How did RedEye happen?

Well, okay then, it was looking like a double-header, not to mention a fine way of wrapping up a week of thinking about how a few paragraphs I wrote in the May 2000 Chicago Tribune strategic plan had turned into something big enough to host a party for more than a thousand of its closest friends:

“Market data indicates that young, time-starved city-dwelling professionals can be be attracted to a newspaper–but that it might take a very different product than the one we produce today . . . Rather than continue to deliver a single newspaper throughout the marketplace and ask its purchasers to make choices from among the content we have bundled together, it may be time to put multiple newspapers in the market and let readers make a choice on what to buy.”

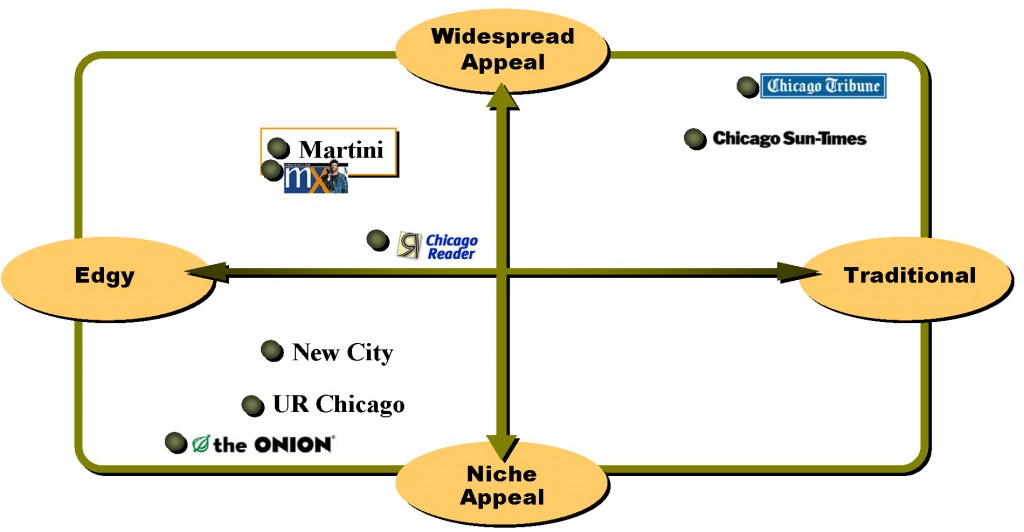

It went on to describe a “5-day-a-week newspaper for single-copy distribution, primarily in the city, Tribune vs. non-Tribune branding to be explored, edited for a younger audience.” But it took another two years before the economics, the competitive situation, and the opportunity came together so that I could assemble a small project team to meet in locked rooms and work through the exercise we called Project Martini (because hey, all top-secret projects need code names, right?). I was going to have a busy year, since we were also working on buying Chicago Magazine; that had a code name too, but I forget it.

John and Jennifer Martini also became the personae we created for our target audience, “young urban commuters” who

- Avidly consume multimedia news; no single medium satisfies their needs

- Define “news” nontraditionally, with an emphasis on entertainment and lifestyle concerns

- Prize relevance, which they measure as much by tone and approach as by content

- Demand that news be formatted, edited and distributed to fit an on-the-go lifestyle

- Respect the Tribune . . . but it’s their parents’ paper.

The Project Martini team saw a place in the market for what would become RedEye. (The closest equivalent I had found anywhere in the world was mX, a commuter newspaper published in Australia.)

Sounds perfectly reasonable now perhaps, but by 2002 the Tribune had been managing perfectly well for 155 years, thank you very much, with a single printed product (though along the way it had bought, renamed, then ultimately closed the tabloid that at the end was called Chicago Today). The research, however, was clear: We weren’t going to attract these readers, or the advertisers who might want to reach them, with a “youth” section stuffed inside the main paper, the method that major metropolitan papers had used for decades to expand their audiences and ad bases.

What followed was a forced march to the fall. A project team in May; editorial, distribution, marketing and ad sales strategies in June; first prototypes in July; technology infrastructure and media planning in August; three rounds of focus groups starting in September, with updated prototypes each time; hiring of staff in October; three preview editions on Oct. 25, 26, and 29; and the official “premiere edition” on Wednesday, Oct. 30, with hundreds of Tribune employees on street corners and at “L” stations handing out samples to unsuspecting commuters.

What followed was a forced march to the fall. A project team in May; editorial, distribution, marketing and ad sales strategies in June; first prototypes in July; technology infrastructure and media planning in August; three rounds of focus groups starting in September, with updated prototypes each time; hiring of staff in October; three preview editions on Oct. 25, 26, and 29; and the official “premiere edition” on Wednesday, Oct. 30, with hundreds of Tribune employees on street corners and at “L” stations handing out samples to unsuspecting commuters.

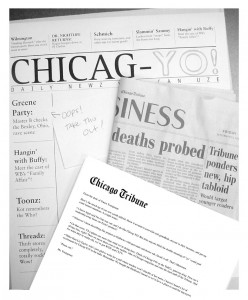

New City took the Tribune news story that we were up to something and ran with it. And ran, and ran. Click image to read my “memo to the staff.”

And of course it hadn’t stayed secret. On Sept. 13 in the Business section, Tribune media columnist Jim Kirk broke the news that his employers were “considering launching another newspaper in the Chicago area–this one aimed at the MTV crowd. . . .It’s not clear how younger readers, who may consider established newspapers stodgy or out of touch with their views, might react to a Tribune-backed alternative paper.” (Can you tell he hadn’t seen our research?)

“While Tribune officials wouldn’t comment on whether they planned to move forward with the new publication, Youngman said cost alone won’t deter efforts to reach out to new readers. ‘Any strategy that we might pursue to go after younger readers will be expensive,’ he said. ‘The question for a media company is what is the right balance of expense and risk and opportunity. We’re not afraid to spend money for an important goal.’ ”

Good thing we weren’t. We spent a boatload for a while, cheerfully offsetting the losses with new profits from Chicago Magazine.

One result of Kirk’s reporting was that on launch day, we had hundreds of Sun-Times employees standing next to us with their competitive response, Red Streak. The hawker next to me in the Loop just kept shouting, “Get your red paper here! Get your red paper here!” A newspaper war was joined, at least until Red Streak ceased publication in December 2005.

Why did RedEye work?

This post can hardly be a comprehensive history of RedEye, or a meticulous retelling of how it grew to become a juggernaut that distributes up to 200,000 free copies every weekday at 4,082 locations around the metropolitan area. Besides, the chronology doesn’t actually explain why it worked. It was several years later, when I read Clayton Christensen’s “The Innovator’s Solution,” that I identified a key part of the reason (in addition, of course, to the brilliant managers and editors, staffers and salespeople, circulators and marketers who turned the idea into reality five days a week): RedEye was a disruptive innovation.

According to Christensen, a disruptive innovation finds its success in part by doing a specific “job” for someone in ways that are simpler, cheaper, and more convenient than the existing alternatives. From the standpoint of John and Jennifer Martini, the “job” of becoming informed while on the way to work . . . in an era well before broadband Internet on a smartphone . . . was being done in an entirely new way.

No, we never should have tried to charge for it. In focus groups, our target audience had told us that whenever they actually had a quarter in their pockets, they either tipped a barista with it or saved it for the laundry. But, once the initial pricing decision had been made and the newspaper war joined, the RedEye launch team under general manager John O’Loughlin and editors Jane Hirt and Joe Knowles executed so perfectly and so consistently that, today, the outcome seems to have been almost preordained: that the “red paper” would join what editor Ann Marie Lipinski had enduringly and endearingly dubbed the “blue paper” as print market leaders in Chicago.

So, happy birthday, RedEye, you disruptor, you. After that party last night, I am hoping to have my hearing back in time for class on Tuesday.