Saturday, September 4, 1971, was cooler than usual in Chicago. The high temperature of 71, 10 degrees below normal, made for a pleasant afternoon trip downtown from the Northwest Side as I waited on the Belmont platform to transfer from the Ravenswood el to an Englewood-Howard train (it was not till 1993 that the various lines were rebranded with colors).

I had last been on the CTA on April 6 – as it happens, the day Richard J. Daley won his fifth term as mayor, receiving 70% of the vote against Republican Richard Friedman. My destination in both cases was the same: the Grand Avenue station, from where I could walk to Tribune Tower. In April, I was interviewing for a part-time job as a clerk – “copy boy,” as males and females of any age in that position were then called. Two days before Labor Day, I now was showing up for my second job in journalism, one of seven rude mechanicals assigned to the 3-to-11:30 p.m. shift.

30 years later, as a “McCormick veteran,” I got a copy of this front page along with a very nice watch. One similarity with 2021: “Cubs Lose Again.”

I had already done my first official assigned task: Reading the 4-Star Sports Final from cover to cover before arriving at the office. We got the 3-Star Home at my North Park College dorm (I’d be starting my freshman year the next week), so I had already invested 10 cents in my professional future.

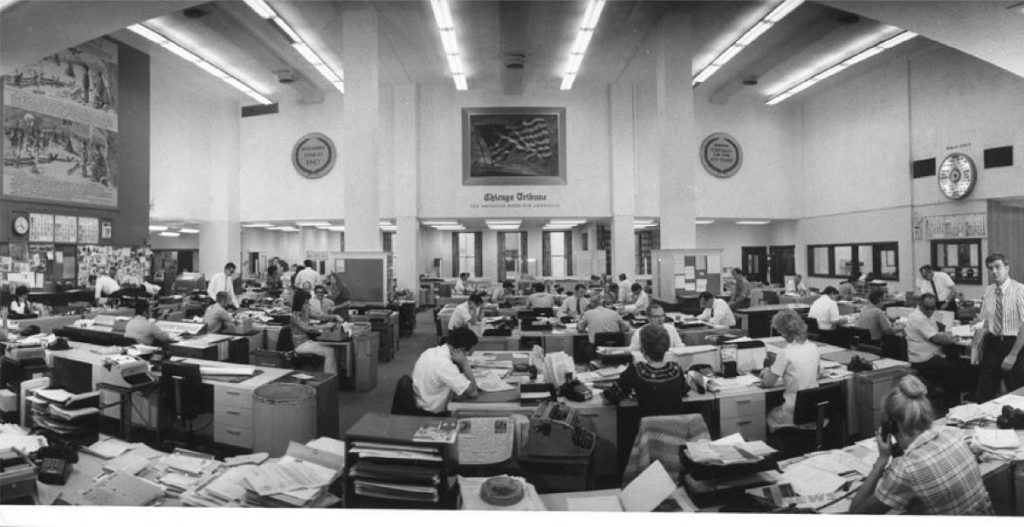

Maybe some other day I’ll sketch out more observations about my 37 years at the Tribune: the dramatic personnel shifts; the prizewinning journalism; the march of new, and newer, and still newer technologies; the “stern stands. And bitter runs for glory,” as in the poem by Stephen Crane – who immediately pointed out that “there were braver deeds.” But for today, let me evoke the room I walked into, just four days removed from my job as a sportswriter at the Ashtabula Star-Beacon. That’s the room you see above.

Compared to a weekday, I was to learn, seven “boys” in the fourth-floor newsroom was a skeleton crew. After all, on the weekend there was no one needing help in the vacant Sunday Room, home to the features staff. The editorial board wasn’t in, either. The editor’s office was unstaffed, which meant that the lightbulb high on the west wall wouldn’t be blinking to urgently summon us. (In fact, on this day, editor Clayton Kirkpatrick was in Tokyo; his interview with the Japanese prime minister was on Page One, if overshadowed a mite by President Nixon’s visit to McCormick Place.) And although Chester Gould could have been in his 14th-floor studio drawing “Dick Tracy” for the 600 or so newspapers that carried it, he typically didn’t need anything on the weekend.

So why we were needed at all? In an era when bits and bytes had barely begun moving across the ARPANET, someone needed to move thousands of pieces of paper around the room and between floors of the Tower.

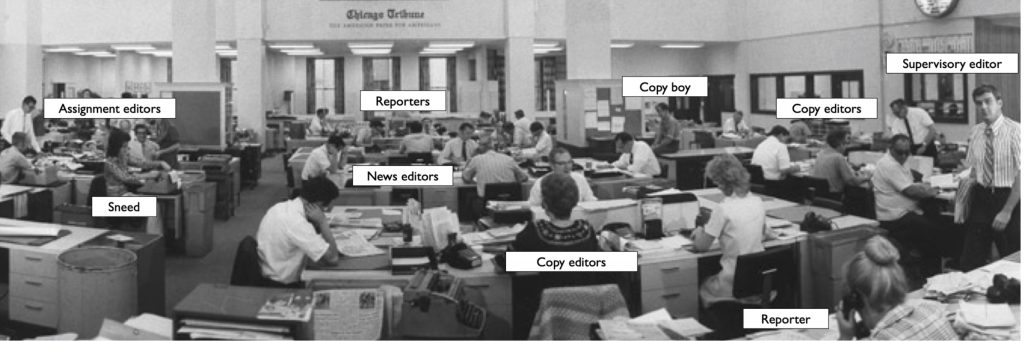

Years later, not long before I left the Tribune for Northwestern, I stumbled across the photo at the top of this page. Blown up to 46 by 22 inches and hanging on my basement wall, it reveals that it was taken just nine days later: Monday, September 13, 1971. For a Medill lecture in a colleague’s class on editing a few years ago, I helpfully labeled it for a class full of students who would never encounter anything remotely like it:

Amid all those journalists sits a copy boy on top of a table. (We didn’t rate chairs unless we were answering phones.) He’s waiting for an editor or a reporter to summon him with one of several time-honored shouts:

Amid all those journalists sits a copy boy on top of a table. (We didn’t rate chairs unless we were answering phones.) He’s waiting for an editor or a reporter to summon him with one of several time-honored shouts:

“COPY!”, say, or “BOY! BOY! BOY! BOYBOYBOYBOYBOYBOY!”

At which the nearest clerk would hop up to grab a piece of paper from one desktop tray and carry it to another, perhaps pausing to separate its carbon copies and carry them to still other trays. The job was to get the destinations right without asking.

(Another part of the job was learning who everybody else in the room was so you could be dispatched to their desks. In this photo, I for sure see Dan McCaughna, Don Agrella, Frank Blatchford, Mike Sneed, Steve Pratt, Bernie Judge, John O’Brien, Carl Sotir, Jim Hallman, Tom Moore, Mitch Dydo, Marcia Opp, Ken Simms, John Gaspar, John Stevenson, Gale Daugherty, Tom Carvlin, and Bill Jones. There are more, but many are blurry even in my wall-sized version.)

Or maybe the shout would be “COPY, DOWN!” Do you see that pillar just beyond the copy boy, the wider one with a bulletin board attached? It’s hiding a pneumatic tube system and a pulley-operated bucket. The pneumatic tube carried edited copy DOWN to the third-floor composing room to be set by a Linotype operator. The bucket carried galley proofs – inky strips of newsprint, placed in the bucket by another copy boy – UP to be proofread. Once corrected, they were lowered for line-by-line repairs, along with page dummies and other items of interest to those in the third-floor composing room.

Blown up to an even larger size on a projection screen in other Medill lectures, this photo might also be viewed as the overview of an archeological dig, in which a careful observer can quickly establish the most common artifacts and perhaps infer their purposes. In ascending order of importance, one can find

- Un-emptyable ashtrays (people just kept filling them)

- Unfillable desktop trays (we just kept emptying them)

- Uncountable newspapers (multiple editions of four competing downtown dailies)

- Push-button telephones (nothing but the latest!)

- Manual typewriters (I remember one electric)

- Large, larger, and enormous wastebaskets (the biggest large enough to hide a person, or two)

Harder to see are other important tools: metal spikes for carbon copies and proofs, scissors and rubber-cement pots for literal “cutting” and “pasting,” and the reference books that amounted to the 1970s version of Google.

What most struck me, having just come from that first job in the (ahem) smaller newsroom of the Ashtabula Star-Beacon, is less visible: the degree of specialization among these professionals. The reporters reported and wrote; the copy editors edited copy and wrote headlines; the picture editors selected photos, cropped them, and wrote captions; the news editors decided what went into the paper and where it would appear. The copy boys moved pieces of paper around, retrieved bundles of newspapers from the mailroom whenever a new edition came off the presses, and bought black coffee for editors, often at the Billy Goat Tavern on Lower Michigan.

For the sports department in Ashtabula, I had done all those things myself, plus taken game photos, developed rolls of film, and made prints by hand in the darkroom, for $1.60 an hour. But in this new joint in those days — though not in 2021, I know — there were whole staffs for each individual task, including me, now a $2.40-an-hour clerk. (That $16 in today’s money, if you’re wondering.)

Before too long, I would decide to stay and try to make a career of it. Maybe, I thought, someday I could be in charge of something. After all, there was lots to write about in Chicago: Woodfield Mall would open in just a few days. The Bears were moving to Soldier Field and would open their season there on Sept. 19. The 100th anniversary of the Great Chicago Fire was a month away. Jesse Jackson soon would found Operation PUSH. . . .

But as noted above, such stories will wait for another day. I think I hear someone yelling “COPY!”