Sometimes I wonder if Leon Durham saved my life by breaking Chicago’s heart.

In October, 1984, you see, I was deputy sports editor at the Tribune, and sometimes it seemed like there was an impossible amount of planning and work to do — because we were covering an impossible number of great sports stories.

- Walter Payton of the Bears was on the verge of breaking Jim Brown’s NFL career rushing record.

- Baseball umpires had decided to strike during the playoffs.

- Two days before the first day of the World Series, no one knew where the first game of the World Series would be played . . . because there were no lights in Wrigley Field, and Major League Baseball would only stand for day games on the weekend.

For sports editors, sleep had become a rumor.

(Oh, did I forget to mention that the Cubs were on the verge of the World Series? Given that, 32 years later, they’re actually in it, I thought you probably didn’t need reminding.)

There were giants in those days, of course — not just Walter Payton and Rick Sutcliffe and Ryne Sandberg on the playing fields, but also Don Pierson and Jerome Holtzman; Bob Markus and Phil Hersh; Fred Mitchell and Bob Verdi and Steve Daley and Bernie Lincicome in the press boxes. And back in Tribune Tower, in those pre-Internet days when Chicagoans counted on their newspapers for every detail in their driveways in the morning, there were an uncountable number of moving parts to account for.

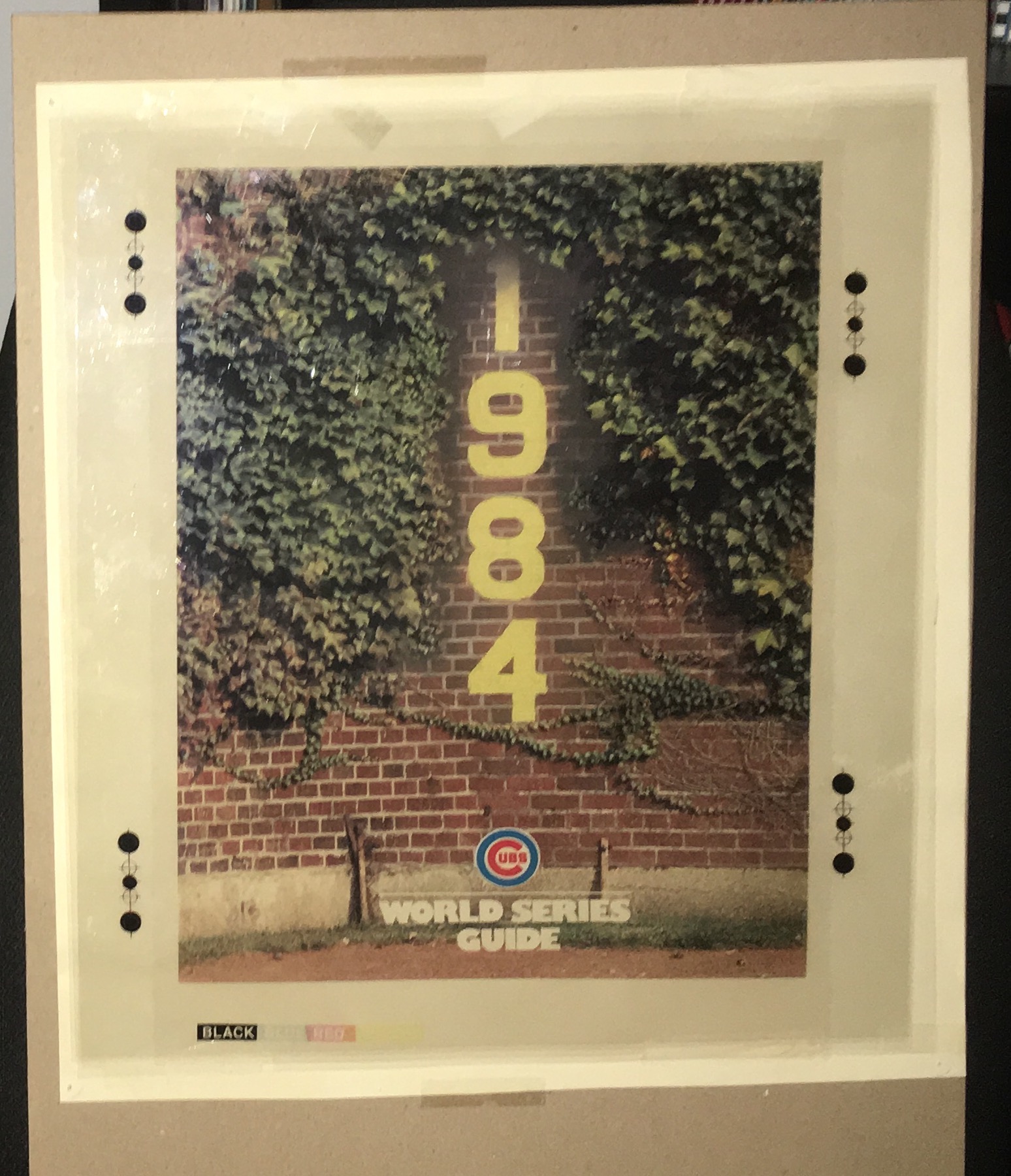

And thus the image at the top of this page. In mid-September I was trying to come up with ideas for a cover image for a special section that would undoubtedly become a keepsake for Cub fans who had been waiting for a World Series for . . . 39 years. Not only did the illustration have to be memorable, but it also had to be ready long in advance — there’d be no way to use a news photo no matter when the National League Championship Series ended, considering how complicated it was to get a color picture of any kind into the paper.

And then I wondered: Could we do something with the bricks, and the ivy, and the bright yellow distance signs painted on the bricks? Could we, in fact, change “355” to “1984”?

Remember, it was 1984. The Macintosh computer had just been introduced. The first version of Photoshop was about five years in the future.

This would not be a question of technology. This would be a job for talented people with hard-to-duplicate skills: a photographer to create the base image on film; a darkroom technician to remove the existing numbers while making a print; an editorial artist to create a realistic rendering of the year where once the distance had appeared. And then any number of craftspeople on the production side to get it ready for the presses.

It took weeks.

Those folks produced what you see above. It is not a single image. It is four pieces of acetate overlaid on one another — the bottom one, entirely yellow; the next, magenta; the next, cyan; and on top, black. Each was required for our presses to combine the four colors of ink in order to create a color image on hundreds of thousands of pieces of newsprint, perfectly matched up so that the image would appear crisp. Those black circles you see up there helped with this “registration” process. It was going to work, it really was.

All the Cubs had to do was win three games against the San Diego Padres, and by Wednesday night, Oct. 3, it was looking pretty good: the Cubs left for the West Coast with a 2 games to none lead, and maybe with any luck they wouldn’t even be playing on Sunday — when Payton had a real chance to set that all-time record at Soldier Field against the Saints.

But by Saturday night, Oct. 6, it had become complicated. The Padres won Games 3 and 4, and the Cubs’ fate would come down to a game at 3:05 p.m. Chicago time, about 5 minutes after the Bears-Saints game concluded with Payton gaining 154 yards to set his record. Figuring on a 2 ½-hour baseball game — can you even imagine that these days? — we would have about 5 hours to put it all together (and cram the two huge stories into the experimental tabloid-sized sports section we were publishing on Mondays that year).

If the Cubs lost, I would then go home. If they won, I’d stay for the production of the special section; half of our editors were poised to drive in from home to work overnight from Sunday into Monday to prepare it — press limitations being what they were, it would have to be printed on Monday afternoon to make the Tuesday paper. And at 4 o’clock, with the Cubs up 3-0, it looked like it would be 10 days till anyone slept.

But in the bottom of the seventh inning, Tim Flannery’s ground ball rolled between Durham’s legs, the Padres turned a 3-2 deficit into a 6-3 lead that stood up as the final score, and life in Chicago — and at Tribune Tower — resumed as before. In Detroit, the Tigers, who otherwise would have hosted the Cubs on Tuesday, instead rushed to the airport and a flight to San Diego.

There was no cheering in the pressbox, in the newsroom, or pretty much anywhere east or north of California. Chicago’s sports editors inserted sleep into our daily regimens. And that World Series guide, and its keepsake cover image, would never see the light of day.

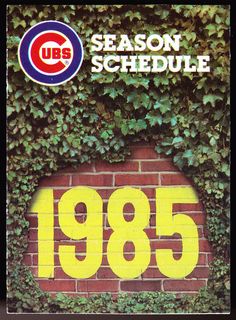

But you might remember that, in those days, the Tribune Company owned the Cubs, and plenty of executives were wandering through the newsroom in October. Proofs of the cover were easily spotted in our offices and on our desks. And in retrospect I guess I shouldn’t have been either surprised or annoyed a few months later, when the Cubs’ 1985 schedule booklet started showing up on retail counters across Chicagoland.

Of course, they had a little more lead time.