It was May 16, 1996. I was riding the Metra train to downtown Chicago when, as I have written before, somewhere south of Northbrook I had my first encounter with the future of American shopping.

Of course, since my iPhone was still 11 years in the future, the event in question was not a retail transaction; it was a Page 1A story in The Wall Street Journal about Amazon.com and its founder, Jeffrey Bezos. Headlined “Reading the market: How Wall Street whiz found a niche selling books on the Internet,” it noted that although Bezos had “pinpointed one of the few products that people really want to buy on line: books. . .few executives in the tweedy book-publishing business know [Amazon] exists.”

Nor did I. They company didn’t advertise much, the Journal said, and I hadn’t yet seen it mentioned in Wired (perhaps too atoms-and-molecules-oriented for that magazine’s early days). I made a note to try “Earth’s Biggest Bookstore,” named after “the river that carries more water than any other in the world.”

It was before Google, so I probably wrote the URL down after I got to work.

I had plenty of books I needed to buy, and I was still mourning the shuttering of Kroch’s & Brentano’s the year before. But — seeing as it was only a couple of months after the launch of chicago.tribune.com — in 1996, I had absolutely no time to browse at Borders or even flip through the Book-of-the-Month Club catalog. So over the Fourth of July holiday, 20 years ago this weekend, I decided to find out whether the people and algorithms in Seattle could actually find books for me that were otherwise out of reach.

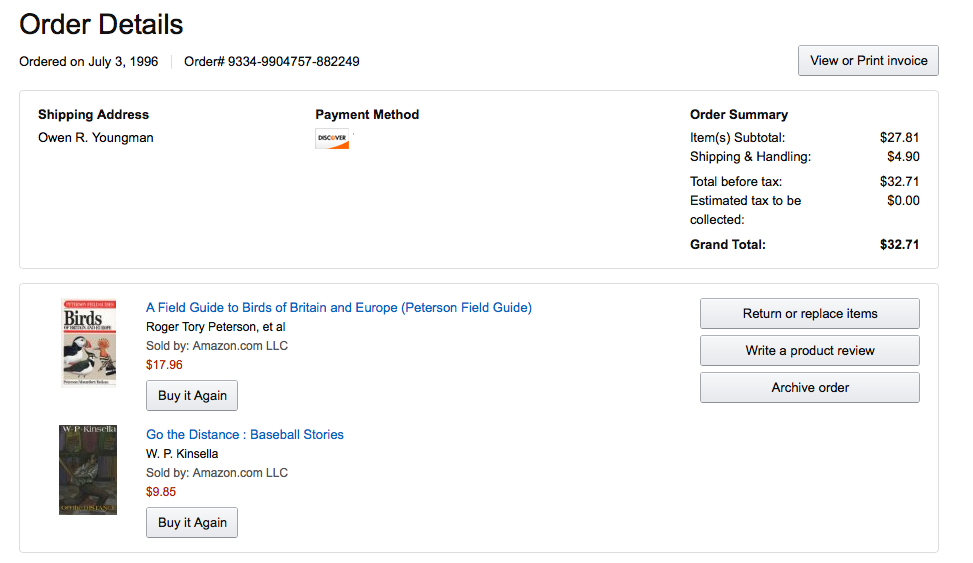

And sure enough (click to enlarge).

One of the things I did on most every vacation was browse in bookstores for books by the Canadian writer W.P. Kinsella, whose main topics are the emotional landscapes surrounding baseball and Native Americans (well, Native Canadians). There had seemed no other practical way to work my way through his oeuvre than to rummage on shelves in out-of-the-way places . . . till now. In addition, I had an urgent need for a European bird guide, since I would be singing in a choir festival in Canterbury in just a few weeks’ time and figured to have time to look up into the British trees.

It was all very utilitarian, hardly something that felt it would become a habit. It wasn’t as relaxing as a book store–hey, even Jeffrey Bezos knew that; the Journal characterized him as “quick to dismiss fears that Amazon could ever spell the end of traditional bookstores. He regularly hangs out at the Elliott Bay Book Co., a sprawling, independent bookstore in downtown Seattle which has exposed brick walls, a cafe and lots of friendly salespeople . . . ‘We are trying to make the shopping experience just as fun as going to the book store,’ he says, ‘but there’s some things we can’t do.’ ”

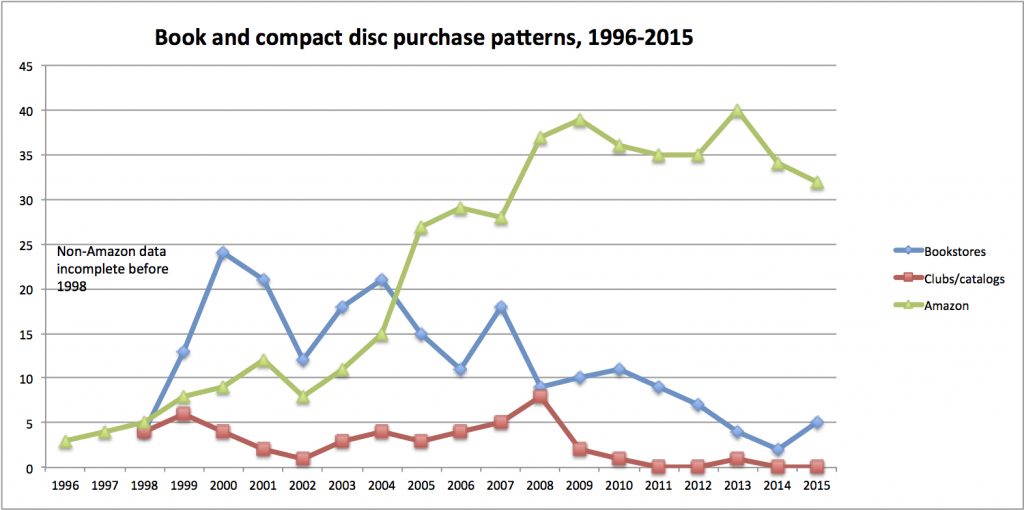

The good news for Seattleites is that Elliott Bay Book Co. is still there. But as I noted in that 2013 post I referenced above, I am one of the millions of people who over time looked up and saw that, good intentions notwithstanding, our cumulative actions meant that local bookstores were disappearing, shrinking, or retrenching to fewer locations; they left the malls, they left the downtowns, they left the strip malls, a sort of reverse-Churchillian litany of response to the invasion.

The good news for Seattleites is that Elliott Bay Book Co. is still there. But as I noted in that 2013 post I referenced above, I am one of the millions of people who over time looked up and saw that, good intentions notwithstanding, our cumulative actions meant that local bookstores were disappearing, shrinking, or retrenching to fewer locations; they left the malls, they left the downtowns, they left the strip malls, a sort of reverse-Churchillian litany of response to the invasion.

Were we sucked in by uncollected use taxes, seduced by Amazon swag (see left for my 1996 and 1997 Christmas presents), or made complacent by yet another delivery landing on the porch in the dead of winter?

According to my data (and perhaps your experience), it was undoubtedly Amazon Prime: Once I plunked down $79 in February 2005 for the illusion of free shipping, the lines in my purchasing-behavior graph crossed forever.  The use and sales taxes are now collected routinely and the swag is long gone, but sometime this year I will place my 800th order with Amazon.com. By my count, “only” about 460 of them replaced bookstore and record/CD store purchases; the rest have replaced daunting forays to Target and frustrating trips to the office-supply store (although Target shopping has gotten easier now that I can use my Apple Watch to guide me through the aisles). And of course, without the so-called free shipping even for single items, I would have consolidated many of those Amazon orders for efficiency’s and parcel post’s sake.

The use and sales taxes are now collected routinely and the swag is long gone, but sometime this year I will place my 800th order with Amazon.com. By my count, “only” about 460 of them replaced bookstore and record/CD store purchases; the rest have replaced daunting forays to Target and frustrating trips to the office-supply store (although Target shopping has gotten easier now that I can use my Apple Watch to guide me through the aisles). And of course, without the so-called free shipping even for single items, I would have consolidated many of those Amazon orders for efficiency’s and parcel post’s sake.

There’s still a Barnes & Noble less than 2 miles from home and another less than a mile from work, but as Norman Maclean wrote in an entirely different context, “Eventually, all things merge into one, and a river runs through it.” Twenty years on and a fair number of books by Kinsella, Halldór Laxness, and Marilynne Robinson later, the Amazon river is floating its own trucks to my door instead of UPS’s. Perhaps the drones will arrive by order 1,000.