Examining time capsules long has fascinated the people who find them. In January of this year, for example, there was quite a foofaraw in Boston over the second opening of a capsule that was placed in the Massachusetts State House dome by Samuel Adams and Paul Revere in 1795. Earlier this week, the CBS Television Networks launched a new channel, Decades, that Robert Feder’s headline called “a daily time capsule,” built around a cultural retrospective hosted by Bill Kurtis.

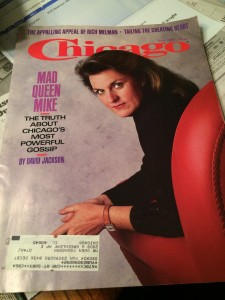

Today, I really get it — because this week my wife and I found one buried in our own home. It’s the July, 1987, issue of Chicago magazine, and it too mentions Bill Kurtis.

You see it above. We had placed it on a closet shelf shortly after moving to the suburbs from Chicago, and it came to light when the shelf came loose this week and I needed to remount and brace it.

The issue takes a reader back to a long-departed world. A world before the Internet, sure, but also a world where the magazine’s two most prominent ad positions — full pages on the back cover and on the inside front cover — are devoted to cigarette ads targeted at women (Virginia Slims and Benson & Hedges), and where the key full-page ads before the table of contents were from Marshall Field’s (“For the way you live”), Carson Pirie Scott (“Carsons is for me”), and Lord & Taylor.

And a world where the Chicago celebrities in the cover story worked in newspaper newsrooms, dissed the people working in rival newspaper newsrooms, and were able to “create issues, make or break reputations, and swing votes.” David Jackson’s cover story on “the power and prominence” of Mike Sneed, still writing in the Sun-Times today, describes a world that seems as remote as the Egypt of the Pharaohs, and as in need of archeology. (Kurtis shows up in the piece stopping at Sneed’s breakfast table at La Tour.)

Sneed was working weekends on the city desk when I showed up at the Tribune in 1971, and Jackson’s piece, “Unmasking Sneed,” is dotted with the names of colleagues and descriptions of feuds that easily resonate with ink-stained wretches of a certain era. Like the rivalry between Sneed and Irv Kupcinet, which didn’t end when she moved from the Tribune to the Sun-Times; perhaps contrasting both their styles and their subjects’ opinion of them, Jackson wrote, “The city named a bridge after Kup. Before they gave the S-curve the wrecking ball, they should have christened it ‘Sneed.’ ”

“One of the quickest ways to get noticed by the big daily papers was to skewer them,” Jackson told me in an email, “and that became one of [editor Hillel Levin’s] assignments [to me], in well stories like that one and a 4000-word front-of-the-book section called Metro. Ironically, press criticism became my introduction to newsrooms, and I fell in love with them.” Except for a year off to help win a Pulitzer Prize at the Washington Post, since 1991 his investigative reporting has been based in the Tribune’s newsroom. (And of course, since 2002 the Tribune has owned Chicago.)

Still, as interesting as Jackson’s piece was to read, it’s just one of the takeaways about 1987 that I derived from unpacking my 176-page time capsule. Here are just five of the others. It was a world where

- Scott Turow was a first-time novelist unknown to the general public. Presumed Innocent, wrote reviewer Laurence Gonzales, “is seamless work . . . the narrative carries us through the finish line without faltering.”

- If you looked hard enough through its authoritative listings, Chicago could help you dine at a 2- or 3-star restaurant for $8 or less per person. Or you could wait for the Taste of Chicago — this issue had 20 pages of advertorial supporting the 8th edition of that festival.

- You didn’t need to look hard at all to find one of Rich Melman’s 32 Lettuce Entertain You restaurants with impossibly long lines for passably good food, enough of them that another feature in the issue was “Melmania!” “What brings people to Scoozi!,” writes Colin Westerbeck, “is the atmosphere of fevered susceptibility, mob psychology, mass hysteria.” Rich Melman knew what he was about: “Suppose I wanted to do a Russian restaurant. . . . If I actually went there, it might ruin my ability to do it.”

- The magazine’s bills were paid, and then some, by liquor, beauty, and hospitality ads, with the random full-page branding ad for Commonwealth Edison far enough forward that you’d notice it.

- All in all, the dining, events, and WFMT listings chewed up 54 of the 151 non-advertorial pages . . . more than a third, given that, well, you sure couldn’t look up that stuff on the Internet.

Not that I could have looked any of this up on the Internet; I needed to open the physical time capsule for myself, in the same way I often pull one of my complete set of Wired magazines off the shelf (not the same shelf, I assure you). That cover picture of Sneed by Jean Moss re-opened a whole world.

“I recall Sneed being really gracious about that piece, and laughing it off,” Jackson said in his email before concluding with one of Sneed’s trademark ellipses: “And I still peel open the Sun-Times to see what’s happening in Scoopsville….”